The drink: an organic blend of apple, spinach, and lime. The topics: machine learning, pareto analysis of healthcare claims data, and data governance. The location, not a Palo Alto juice bar, or Scandinavian coffee house, but Manila, Philippines. In a feng shui take on an ultra modern coffee shop on the second floor of one of Manila’s many new real estate developments, Dr. John Wong, the recipient of the 2016 Roux prize, and I talked about the role of data in prioritizing resource distribution, detecting fraud, and identifying corruption in universal healthcare.

PhilHealth (Philippines Health Insurance Organization), the government controlled Philippine corporation has spearheaded the universal health coverage movement in the Philippines for the last 20 years. However, financial deficits, few restrictions around what type of care is covered, and rampant fraud have made implementation of its vision challenging.

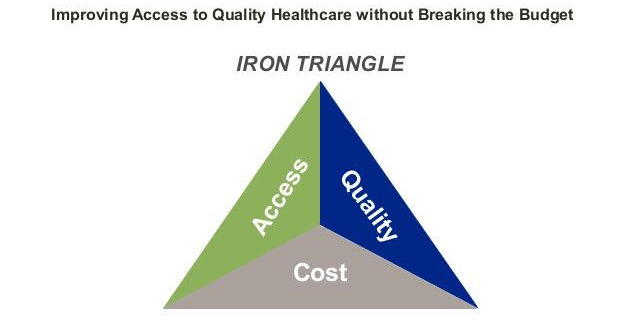

It helps to understand the constraints an organization like PhilHealth faces in healthcare. To do so we introduce two shapes: the Iron Triangle, and the Universal Health Care (UHC) cube. The iron triangle geometrically portrays the healthcare utopia of easy access to healthcare, with high quality, and at low cost. Most health systems in reality could only ever choose to optimize one, maybe two while hoping to keep the second and/or third vertices constant.

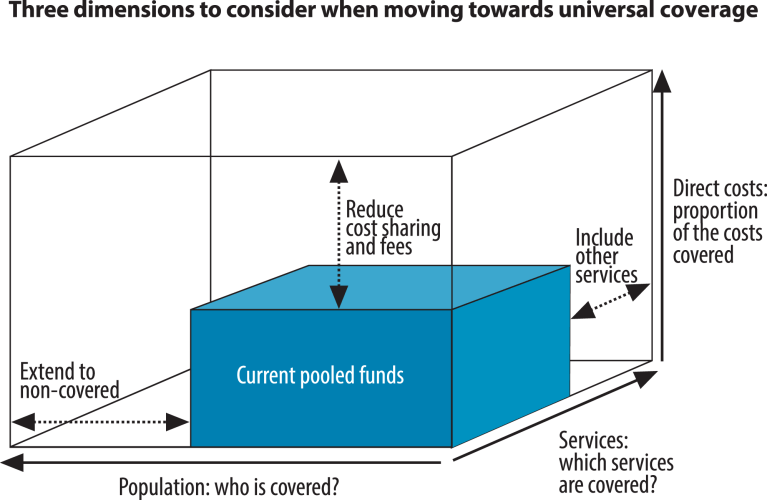

The UHC cube helps break down the levers available for a country to address one or two vertices of the iron triangle, and consists of “population “on one axis, “services offered” on a second, and “percent of cost covered” on a third. In the Philippines, PhilHealth covers 92% of the population, and until recently, PhilHealth covered all inpatient procedures. They would, for example, cover wart removal, but not outpatient care, including routine checks like blood pressure. At one point a transplant surgeon headed the agency. Renal transplants were subsequently covered under PhilHealth, diabetes screenings were not, even though diabetes is usually what causes the end stage renal failure that necessitates the transplant.

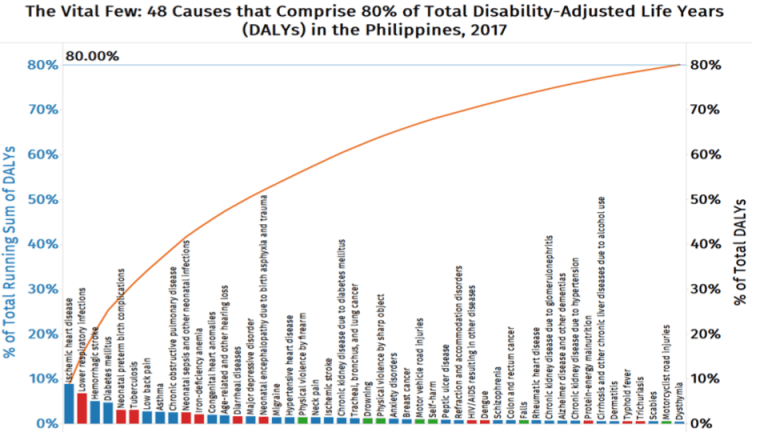

A team at EpiMetrics (https://www.epimetrics.com.ph/) led by Dr. John Wong performed pareto analysis using the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation’s Global Burden of Disease Study to stratify and prioritize the most pressing needs for PhilHealth to address. Such prioritization had never taken place, and while PhilHealth is still working to implement changes to reimbursement procedure to leverage the analysis’ findings, it marked a significant step forward in addressing inefficiencies in delivering efficacious universal care, a step powered by data.

Through their research they discovered that

- 40 diseases account for 80% of the burden

- 10 account for 40% of the burden

- Non-communicable diseases will account for the majority of the incident burden in 2040

Fraud detection:

Until recently, fraud detection meant randomly checking paper files by hand, and in a country known for its corruption (117th out of 190 countries in the World Bank’s doing business index), the agency responsible for financing its healthcare is no different. Outside of its own internal corruption, PhilHealth loses billions of Pesos each year ($1 USD ~ 50 Pesos) to fraudulent claims made by physicians, physicians who overprescribe and perform tests that patients do not need. As one healthcare entrepreneur in the Philippines put it, “Doctors are like politicians, but instead of stealing money they steal lifespan.” A parody of PHIC (Philippines Health Insurance Corporation, another name for PhilHealth) satirizes the common methods of claims fraud

- Pneumonia: If a patient comes in with Pharyngitis, they will admit the patient with “pneumonia”.

- Hemodialysis: If a patient requires peritoneal dialysis (PD), they will bill for hemodialysis (HD) (both perform the action of the kidneys, not only is HD more expensive, but is also more excessive for a patient who only requires PD).

- Influenza: If the patient comes in with a common cold, a few days later the physician will submit a claim for influenza

- Cataracts: Filipino doctors have been known to send “agents” to find patients in rural areas with eye problems just so they can perform cataract surgery on them

Several years ago the Philippine senate summoned PhilHealth to explain the reasons behind their fiscal deficits (PhilHealth ran a 4 billion peso deficit in 2017, an almost 200 percent increase from the previous year). Enter Epimetrics yet again. This time, they had partnered with Philippine run artificial intelligence company Thinking Machine (https://thinkingmachin.es/). Because of challenges in data governance in the Philippines, they were not able to use true machine learning, but were able to use more basic data analytics to identify outliers. As a result, this gave PhilHealth’s auditing team a more strategic and informed approach than randomly checking claims.

As my next post will detail, corruption and poor data governance have severely hampered efforts in effectively using data for universal care, but Dr. Wong’s work in the Philippines reveals a powerful tool at the disposal of countries looking to make steps toward universal care.